Task analysis serves as the foundation for instructional design. In order to meet any need through a training or learning activity, you have to first be able to describe what you want your learners to think and perform. And then from there, you can proceed to build your training, assessment, and evaluation. But how do you articulate these learning outcomes and the steps to get there? The answer is: task analysis. And here are the three types of task analysis, including job/task analysis, learning analysis, and subject matter analysis. Understanding what they are, what they do, and how to use them correctly can help your learning and development team improve organizational performance that increases revenue.

Job/Task Analysis

A Job/Task Analysis (JTA, J/TA, or J-TA) is one of the most common types of task analysis. This activity takes a very close look at role or position at a business, and outlines all of the tasks that the person who performs that function does. The tasks of the role are organized and classified into a structure that makes reviewing the larger picture easy and fast, with the ability to also drill down into the specific component parts. If you are trying to deliver measurable business process improvement to raise quality, it is a critical starting point.

For example, consider a person who works as a cashier at a fast food restaurant. The domains, or larger level functions that they perform in their role, probably include:

taking customer orders,

gathering food from where it is prepared, and

cleaning different areas around food preparation or retail service.

The medium level below each domain items is called tasks, which could include taking breakfast orders, coffee orders, and lunch orders.

And then drilling down into the specifics of each of those tasks, would be the sub-tasks. Things like operating the headset and navigating the breakfast menu.

So to summarize, J/TAs essentially answer the question: What does a person in this role do?”

Learning Analysis

While a Job/Task Analysis examines the way a job is performed, a learning analysis describes the job or role’s tasks in the ways that they are best learned by the target learner. And that may actually be very different from the way the job is currently performed, especially if you have a portion of your population of learners who have accessibility needs. There are three things that a learning analysis might include: learning hierarchy, information processing analysis, and learning contingency analysis.

Learning hierarchy

Also known as a prerequisites analysis, a learning hierarchy lists the information that needs to be mastered before the job can be done. It is useful in ferreting out assumptions about knowledge a learner may have to bring to the role, as opposed to learning through specific training. You can begin by identifying the most complex learning outcome that is sought for the position, and then you should list the prerequisite knowledge, skills and abilities (KSAs). Once you have the prerequisite skills for all tasks, you can then build a learning hierarchy.

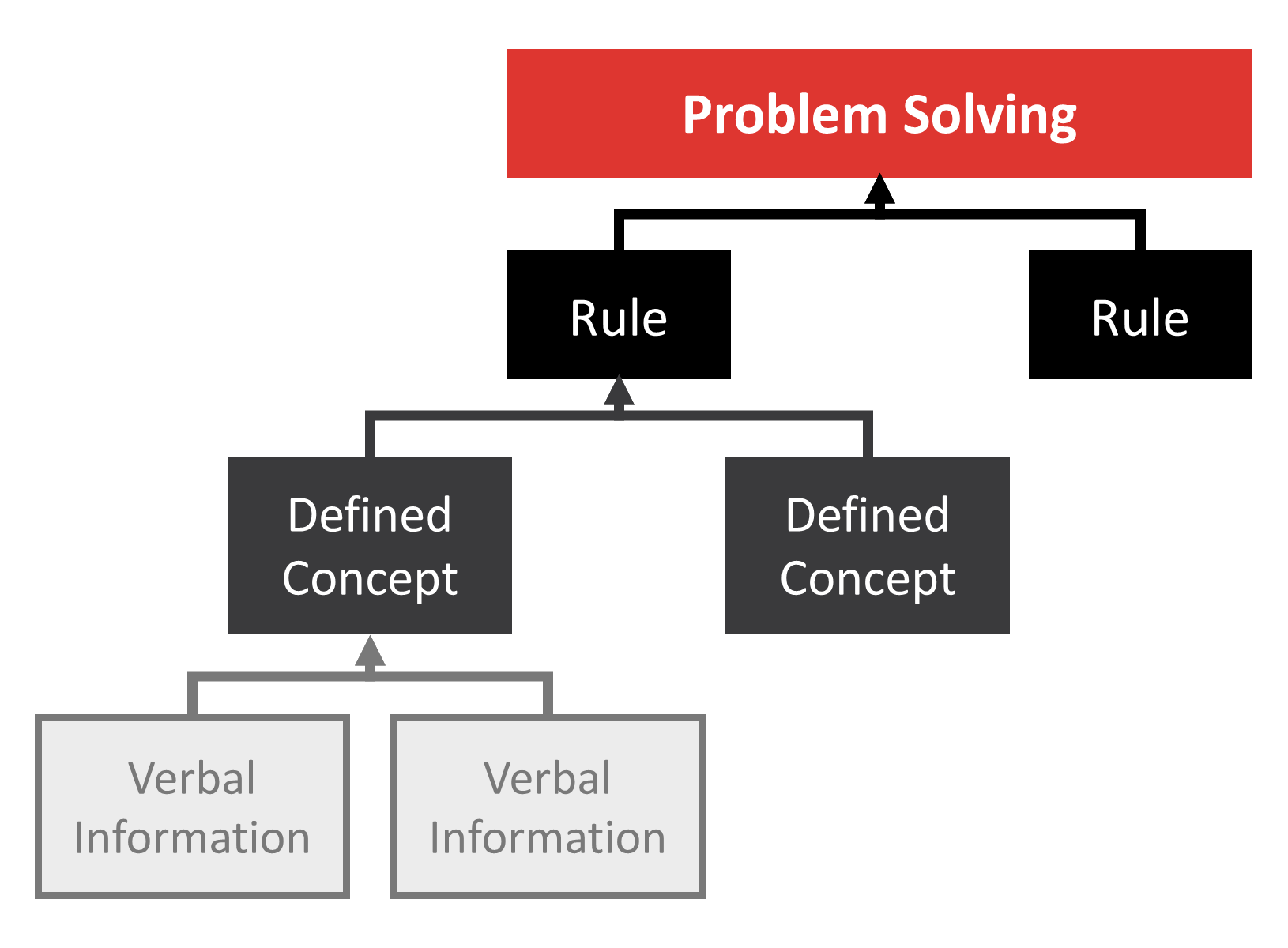

A hierarchy breaks down each task into rules, defined concepts, and verbal information. This analysis can be used to diagnose why someone isn’t learning. Because if they haven’t mastered the prerequisites, then they likely won’t be able to learn the new material. And the hierarchy can also be used to plan curriculum maps of intellectual skills, which is useful for talent matching.

Information processing analysis (IPA)

This is unlike the other analysis discussed, which have all been about identifying overt behaviors. Instead, the information processing analysis (IPA) seeks to identify the mental processes needed to complete a task. To be clear, they don’t have anything to do with learner motivation or readiness to change. Instead, they are all about the person’s ability to take in and convert information to tasking, at the highest level. The IPA essentially outlines the thought process an expert would have. And the result of an IPA is a sequential outline or algorithm, which is very useful for higher-level tasks such as problem-solving, or applying rules or principles to individual, varied situations.

These types of tasks often do not have a clear-cut, correct answer. They are more about how things get figured out. So it’s the mental process of getting to a solution that is the most important. And for many people, that can be the most difficult part to learn. As a result, by mapping out the desired thoughts, you can make a huge impact on the design of any instruction, including eLearning courses, face-to-face trainings, or even learning in the flow of work.

Learning contingency analysis

Sometimes we talk about tasks in a way that makes them seem independent of each other, but in reality, everything works together in a system. The learning contingency analysis focuses on the inter-dependencies between tasks, such as the sequence of activities or knowledge that is best absorbed by the target learner.

Questions that a learning contingency analysis answers usually include:

Which tasks or sub-tasks must be completed before the other?

How do they interact?

What tools, resources, or people are used between tasks, and how might that make an impact?

For instance, let’s imagine you are seeking to improve customer satisfaction in the energy sector by developing a high-quality, new hire training for solar panel technicians. They will need to learn the technical knowledge about how the panels work and how to navigate around them. They will need to be able to adjust those tasks for varying installation types or locations that are arranged in different spatial patterns and configurations. But they may also need to be able to:

Get themselves to the job site,

Do a site assessment before performing any maintenance,

Gather the tools they need before leaving, and before going up onto a structure,

Communicate their position to the dispatch center, and

Be able to access reference information by manual, smart phone, or laptop while they are working

Each of these items relies on some prerequisite knowledge that can create distractions or can impact the learner’s schema, if they are not considered and discussed properly within the training. By performing a learning contingency analysis, you help ensure that each learner takes in and absorbs the knowledge as intended, so that they can complete their job according to expectation.

Subject Matter Analysis

When you start an analysis, both designers and subject-matter experts (SMEs) usually outline the material that needs to be learned. However, when you break things down into an outline, you are essentially turning the material into a procedural structure. Sometimes that is the best way to teach the material, but other times, the material is better served by a conceptual, theoretical, or other type of structure. A subject matter analysis:

looks at the material,

analyzes what the best structure for it, and

presents the material in that structure.

So what exactly are different types of content structures? There are numerous ways you can approach structuring information, but here are three examples to demonstrate:

The most common form of a content structure is an outline. First you cover A. Then you cover B. Then C, and so on. You probably already have some experience with this familiar and conventional approach.

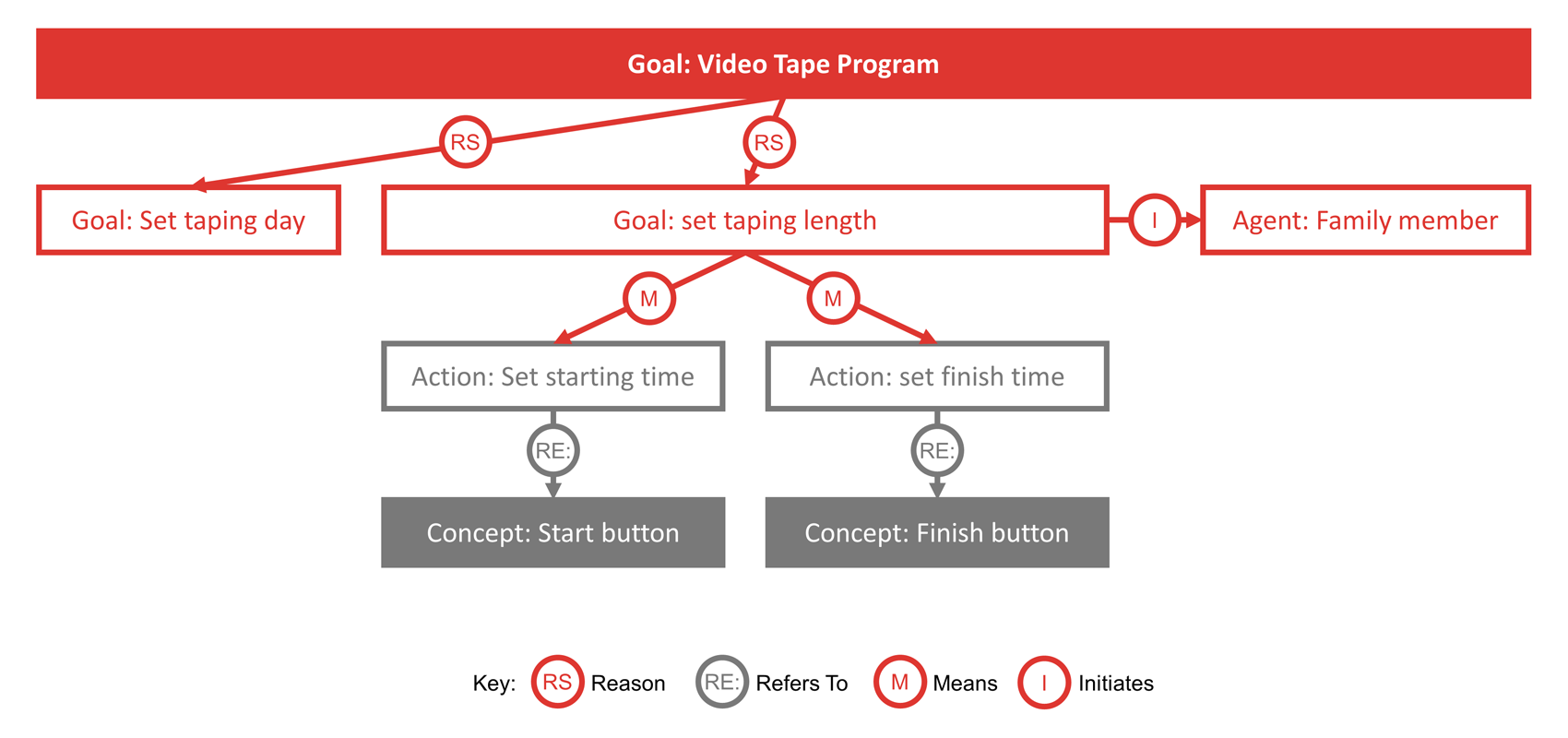

Another type of content structure is a concept map, or even a more formalized conceptual graph. This approach maps out concepts, actions, events, and goals into an overall flow. It can be very useful if you are building an instructor-led training on a budget. Instead of linear thinking, it makes the material into a more complex web. This is an example of a conceptual graph for videotaping a TV show:

Often times with an outline we jump straight into the lesson that we want to teach. However, by focusing on the detail first, rather than the overarching course or program, we may not be teaching the material in the most effective way. A master design chart takes a higher-level look at the entire curriculum, mapping out the topics and desired behaviors. This keeps you from getting “stuck in the weeds”, and instead ensures that the overall learning goal is met. Obviously mapping out everything in an entire curriculum is a much larger ask than just one lesson. But if you keep everything in one table, you will be able to see exactly where in your curriculum you are covering each topic.

Bonus Analysis: Needs Analysis

A needs analysis is not technically a task analysis because it relates to the organization instead of the role. However, it is useful to differentiate between the two because you can use a needs analysis to determine if learning actually solves an identified need, as well as how serious the learning need actually is. This can help reduce damaging assumptions that undermine business performance.

A needs analysis answers the question “Can I solve this problem with learning?” instead of “What must be learned in order to meet the goals?”

After performing your needs analysis, you will have a prioritized list of learning goals which will definitely impact the solutions that are informed by a job/task analysis, learning analysis, and subject matter analysis. Therefore, it is very important to complete your needs analysis BEFORE you begin the task analysis process.

Written by Melissa Lambert, M.S. and published in 2023.

Subscribe to our newsletter today to automatically receive the next issue in your email inbox.

Related Articles For Further Reading